Functional orthopaedics in dogs – Husky Dante

The patient we have the opportunity to present today has been showing right front hang-leg lameness since January. This case not only demonstrates how functional orthopaedics works – it also shows how it can help even “hopeless” patients.

The husky Dante was presented to the in-house vet with a suspected muscle strain. However, anti-inflammatories and physiotherapy prescribed beforehand did not bring any relief. Therefore, he was presented to our practice in April.

Functional orthopaedics

Functional orthopaedics deals with orthopaedic structures and their pathology. In particular, it is concerned with mobility. This includes:

- The degrees of freedom of joints and limbs.

- Structural physiological and pathological findings.

- General (dys)function of the joints as well as

- Regional orthopaedic structures (such as at the pelvic girdle or spine).

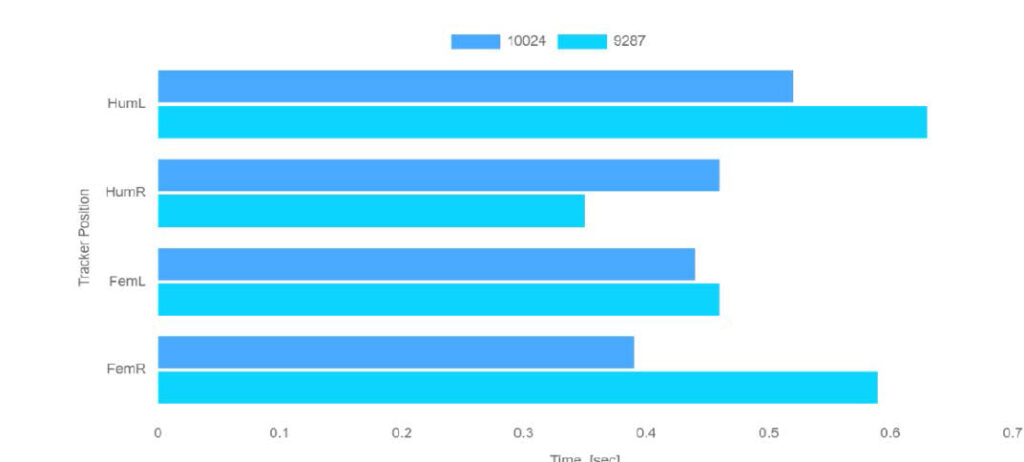

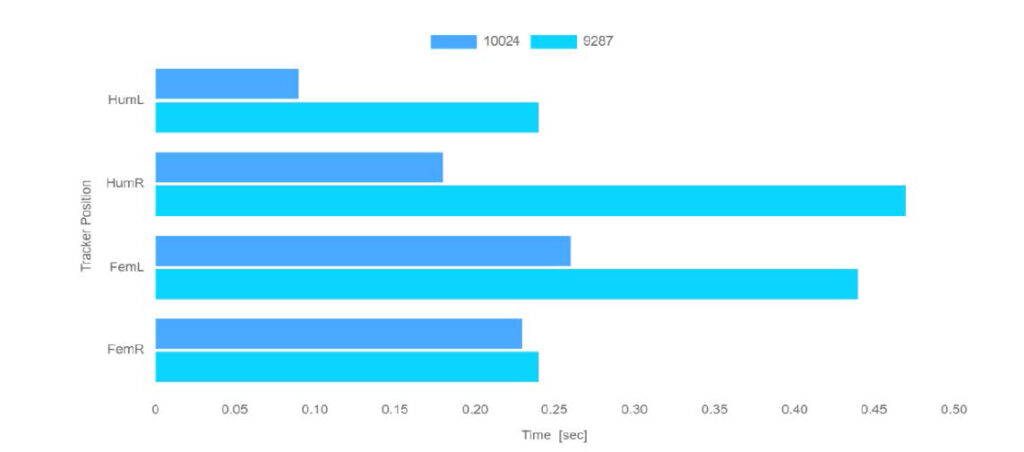

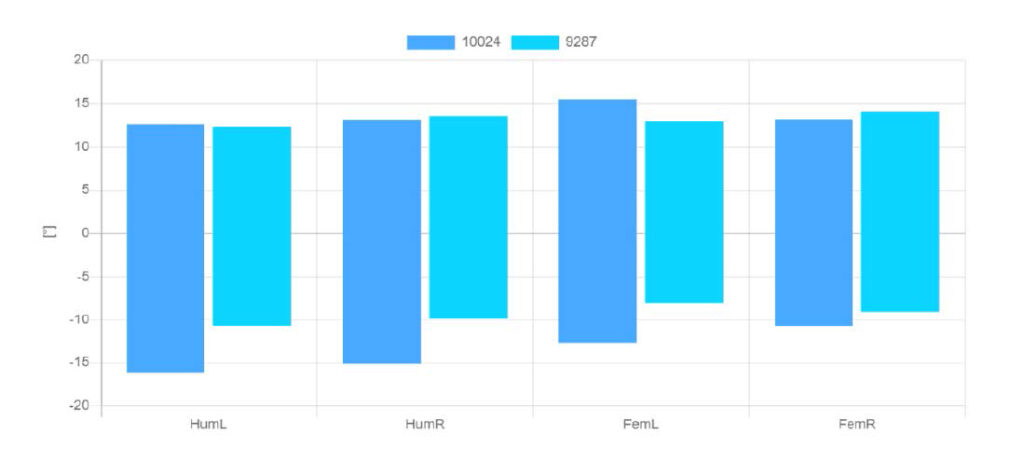

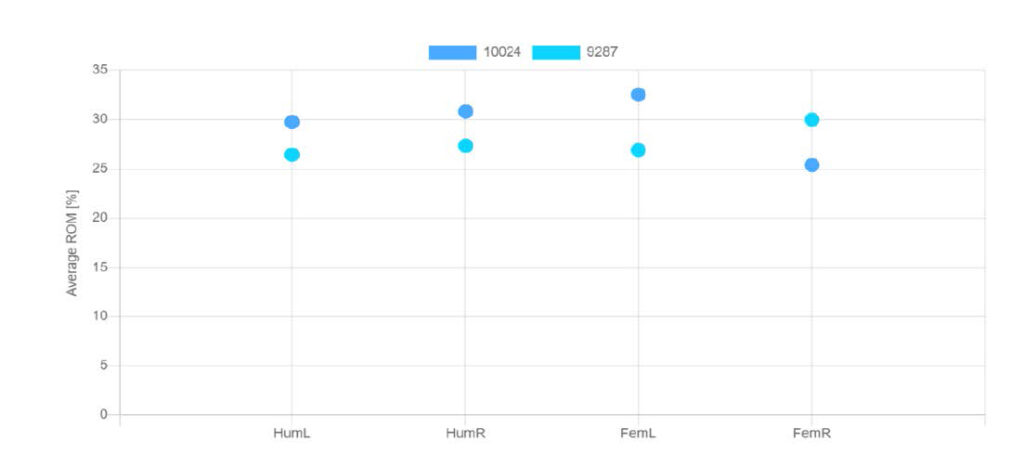

In the case presented here, the dog’s shoulder is the focus. The terms Range of Motion (ROM) and Range of Freedom (ROF) play a special role. They provide information about the function or – in this case – the dysfunction of a joint, whether it is normal, altered, or even physiologically or pathologically conspicuous.

The examination of functional orthopaedics, like all specialisations, demands a great deal of time and experience. It also requires a lot of time and experience to recognise breed-specific changes in the dogs. The treatment differs greatly, also with regard to the size and mass differences of the patients. In addition to experience and time, a fine instinct is required to meet the individual requirements of the patients.

The goal of functional orthopaedics

In a nutshell: Dogs are orthopaedically examined to detect and treat structural changes.

It is generally assumed that a lameness in a dog must be caused by dysplasia, osteoarthritis or some other defective structure. This assumption is largely correct: 50-60% of lameness in dogs can be attributed to this. The rest of the cases, however, have a functional cause.

It can be stated that in these instances, the statics or dynamics are altered without structural pathologies being present. These cases are usually related to the architecture or anatomy of the dog.

Where is functional orthopaedics in dogs important?

Without going into great detail, this is particularly the case with the

- Shoulder girdle and

- pelvic girdle.

The shoulder limb mass in dogs is important precisely because, unlike in humans, it is not structured as a rotator cuff, but as a synsarcosis. In concrete terms, this means that the shoulder limb mass is connected to the rib cage by a flange and can therefore slide along it in a relatively unstable manner. ROM and ROF play a special role here.

Another point is that many canine shoulder pathologies are cases of soft tissue pathology. As a result, many pathologies cannot be diagnosed by X-ray, ultrasound, MRI or CT. Therefore, in addition to the aforementioned sensitivity of the orthopaedic examination, functional diagnostics are indispensable. This includes gait diagnostics with the “Inertial Sensor Unit” or IMU for short.

The pelvic belt is similar. It is connected to the spine in the same way; the so-called ileo-sacral joint is a 70% connective tissue connection between the iliac-peel joint and the sacrum. Important about the pelvic girdle is the number of exposed nerve endings. Also other receptors that regulate mobility and especially pain nociceptively. Also with this connection, the proportion of soft tissue defines the region.

In dogs in particular, this area, the cauda equina, is very important for the pathology of the hindquarters. In puppies, the pelvic girdle provides the anatomical structures for hip development; in young dogs, it is significant for training and movement development. And in middle-aged dogs, this is where disc pathologies begin.

It can be stated that this lumbo-sacral instability in connection with the pelvic girdle plays a decisive role in the onset of weaknesses of the hindquarters and pain.

What principles does functional orthopaedics in dogs follow?

When we talk about functional orthopaedics, we have to keep the following aspects in focus:

- Stimulus-response principle,

- Form-function-changes, the

- Arndt-Schulze rule and the

- Adaptability of orthopaedics.

Let us first look at point a), which is also taught as “actio=reactio”. Specifically in dog medicine: If the dog romps and plays unrestrained and eventually falls violently, this has consequences. These can occur immediately, but also with a delay. It is precisely this that must be taken into account in the case of lameness of the shoulder or pelvic limb masses.

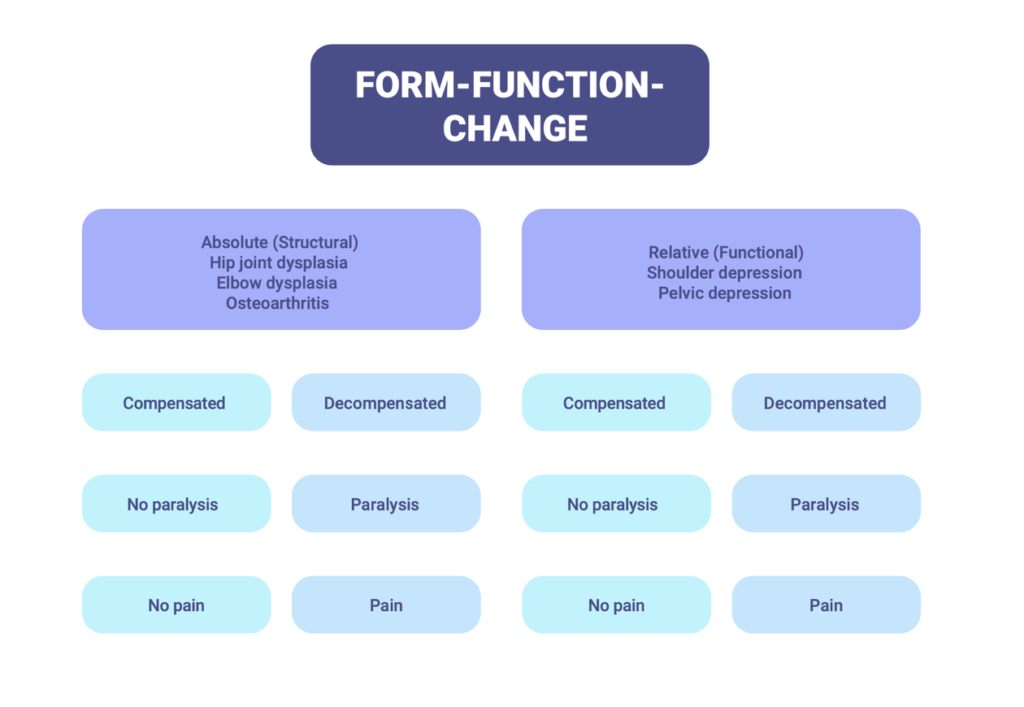

Point b) also comes into play here: a pathology can be structural or functional as well as absolute or relative. In hip joint dysplasia, for example, one speaks of an absolute form-function change. One speaks of relative pathologies in connection with pain in the ISG or a tilted pelvis in the high or low position.

The Arndt-Schulze rule can be explained very briefly. Every physiological movement trains and promotes the stability of the skeletal system as well as the musculature. On the other hand, overstraining movement or overtraining can have pathological consequences. Basically, it is a matter of moderation. This motto is especially important for growing puppies.

The adaptability of the orthopaedic system can have positive effects. It can mean that the consequences of endurance, strength and speed training are transferred to the orthopaedic system at all times. On the other hand, however, there are also negative consequences.

A practical example is the hopping of smaller dogs. Normally this is associated with the dogs’ patella. However, if the habitual patella is not the cause, there is often no explanation. Generally, the bouncing is subsequently treated as a “tic” – which is absolutely not true. After all, the dog does not show any orthopaedic compulsions or comparable behaviour. Functional orthopaedics provides information here and attributes the problem to the biomechanics of the pelvis. Through romping, playing and uncoordinated movements, these biomechanics changed, while the growth plates are still open due to the dogs’ young age. These changes are subsequently reflected in the pelvic limb mass. Variations in statics result in variations in dynamics. Bouncing is a countermeasure designed to compensate for specific differences in frequency, step or stridelength. A suitable analogy is a differential in automobiles: This compensates for differences in wheel revolutions of the axle, for example in curves.

It is also worth mentioning at this point, in addition to functional orthopaedics, the role of functional neurology – also in relation to the bouncing of smaller dogs. More of this at another time.

In summary, it must be stated that functional orthopaedics and thus statics and dynamics must increasingly find their way into veterinary orthopaedics – with the inclusion of biomechanics and its rules. Functional diagnostics will provide the necessary basis for the treatment of non-structural disorders.

You can also watch a video of Dante’s case:

For more information on kinematic gait analysis and the correct build-up of puppies, take a look at our book “LUPOMOVE® PUPPY – THE INNOVATIVE DEVELOPMENT AND PROPHYLAXIS PROGRAMME FOR PUPPIES”.